In recent years, there has been increasing discussion about the development of an innovation-based economy, about how to increase the share of high-tech products in GDP, raise labour productivity, turn knowledge into money and elevate the economy to a new level. One might think, what could be simpler? After all, science and innovation are indeed the most important drivers of economic growth. However, if one takes a closer look at the countries of the former USSR, the situation turns out to be far from straightforward and linear.

Many post-Soviet republics actively declare their commitment to innovation, but in practice, the knowledge intensity of their economies remains extremely low. Paradoxically, even with chronic underfunding of science, economic growth in a number of countries continues — which at first glance seems puzzling. Why does this happen and how can this phenomenon be explained?

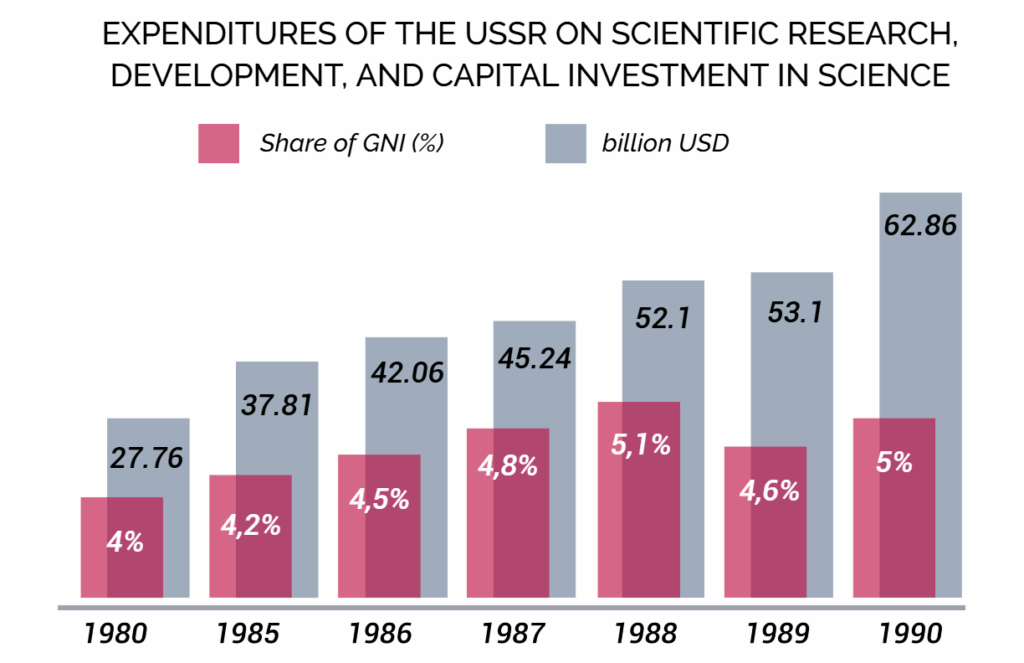

In the Soviet Union, science and technology were a national priority. By the late 1980s, the USSR employed about 1.5 million scientific staff — almost a quarter of all scientists in the world. Thanks to these investments, the Soviet Union was able to compete with the USA in the most advanced fields: nuclear energy, space exploration, physics, mathematics, biology and others. After the collapse of the USSR, it seemed that each republic would at least retain part of its scientific potential, develop it and use it as a basis for an innovation breakthrough. But things turned out differently.

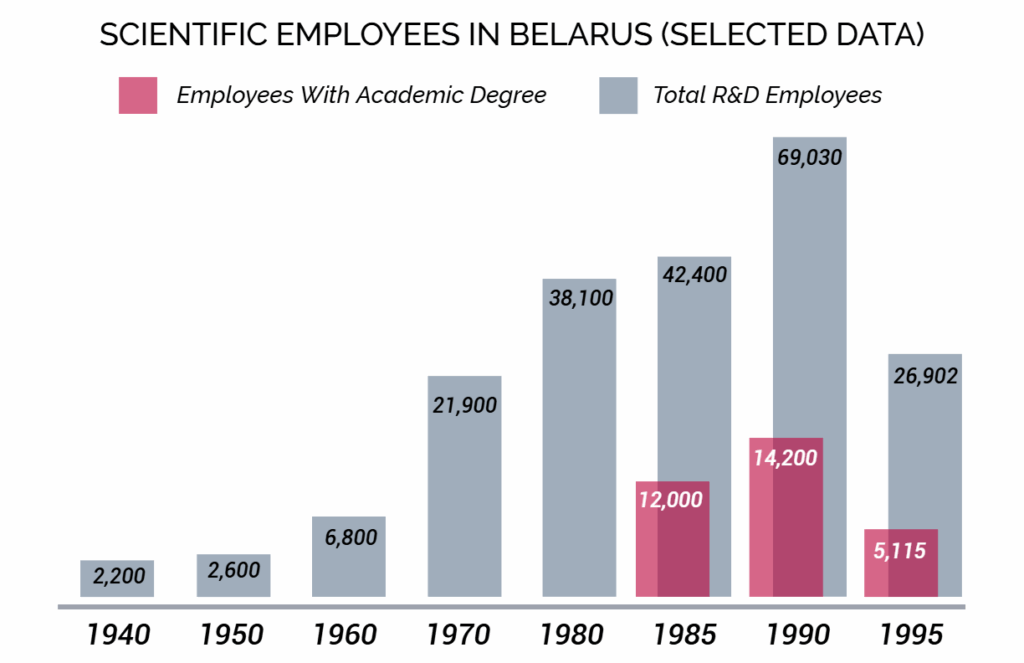

Most countries in the region have sharply reduced their spending on science, and the share of R&D in their GDP does not exceed 0.2–0.3%. Even in Russia, despite its scale and economic ambitions, this figure does not reach 1.1%. Only certain sectors, such as the aerospace industry or nuclear energy, stand as exceptions. In Belarus, over the past three decades, the number of scientific personnel has decreased from 70,000 to less than 27,000. The average age of researchers has increased, and a significant proportion of doctors of science have passed the age of 70. The economy effectively continues to rely on the achievements and groundwork established back in Soviet times.

So how is it that under such conditions some countries still manage to show economic growth? The answer lies in the effect of “deferred investments” in science and human resources made during the Soviet era. These investments are still yielding results today — for example, Nobel Prizes awarded for discoveries whose roots trace back to the Soviet period: quantum dots, graphene, achievements in physics and chemistry. But it is important to remember that this resource is gradually being depleted. The potential of the old scientific school is declining, and new investments are often too modest to compensate for the losses.

The charts and diagrams presented in the article clearly show that, for example, in Belarus, GDP is demonstrating steady growth, while the share of high-tech sectors in its structure continues to decline. This breaks the familiar model: “the more science, the higher the economic growth.” Does this mean that science is no longer important? Absolutely not. In fact, it merely proves that at the current stage of economic development, other factors are starting to play a decisive role: the institutional environment, political stability, social policy, effective allocation of resources and personnel policy.

Belarus demonstrates an important feature: even with minimal funding, science is still able to support the economy thanks to the groundwork laid in the Soviet era. However, this trend is not endless. To move forward, countries need new investments, support for young researchers, modernisation of scientific infrastructure, and increased international cooperation. Without this, the “deferred effect” will stop working, and countries will face an acute shortage of technology, a brain drain, and a decline in competitiveness in the global market.

The experience of the post-Soviet republics shows that supporting science is not just a line in the state budget, but a strategic investment in the future. Every decision in this area affects growth rates, living standards and the country’s position in the global economy. And the sooner politicians and businesses understand this, the greater the chances of preserving and multiplying the legacy rather than squandering it to the end.

Alexander Kozlov,

Candidate of Economic Sciences, Associate Professor,

Deputy General Director of the State Scientific and Production Association “Scientific and Practical Centre of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus for Materials Science” for Economics and Production, Minsk.