Lessons of the Hot Days of ‘Kazakh Winter’ for Central Asian Integration

Disturbances in first half of January 2022 caused by popular unrest in Kazakhstan can be remembered as the ‘Kazakh winter’ – events which shocked the very foundation of the political system of this state. They revealed a deeply rooted vicious regime of diarchy which the first President of Kazakhstan N. Nazarbaev created – the regime of the power of him, by him and for him (to paraphrase Abraham Lincoln’s dictum: “Democracy is the government of the people, by the people, for the people). This ‘Kazakh winter’ revealed a very controversial, perplex and dangerous development of the state.

It wasn’t controversial, perplex and dangerous only for Kazakhstan but also for the whole Central Asia which will likely face direct or indirect challenges related to the situation in this Central Asian country. What kind of challenges? They are twofold; it should be noted that: 1) each individual Central Asian country side by side with its own specific problems, experiences similar problems to Kazakhstan; 2) all five countries of the region are regionally interconnected, interdependent and are engaged in a regional integration process.

In the wake of the “Kazakh winter”, it becomes obvious that the Kazakh President has two options: to consolidate his own power at the expense of democratic reforms or to speed up reforms with some risk for the autocratic political regime. Similar options do exist in all countries of the region (just like in all authoritarian countries of the world). Therefore, some lessons should be taken by all in the region.

Throughout independence, Kyrgyzstan has been moving from “revolution” to “revolution” and has already seen 6 presidents. Its symbolical image of the “island of democracy” in Central Asia appears to be a myth. Turkmenistan has moved from one dictator to another one. Tajikistan has been developing under one president all this period since the end of the civil war in 1995. Uzbekistan has a second president who came to power after death of his predecessor. Finally, Kazakhstan has experienced a “two-presidents” system until the overthrow of the first head of the state and transit of power ended up with country-wide popular unrest. None of these Central Asian countries have been able to manifest themselves as a democratic/democratising/liberalising polity. So, political systems of all Central Asian states are quite similar to each other, in one way or another way.

Moreover, the tasks of democratization are actually the same everywhere, since they imply a checks-and-balance system of powers, existence of independent opposition parties, independence of the judiciary, independence and high authority of the parliament, active civil society and so on. From this point of view, one can assume that similar social, economic and political problems will likely cause a similar reaction on other parts of the population.

Another important lesson is in relation to what can be called the “test of unity”. Unity and regional integration of Central Asian countries can be challenged in the context of the “Kazakh winter” in two ways: 1) countries concerned can take an isolationist stance with respect to the country-in-unrest in order to prevent any spill over of disturbance across the borders and reduce the probability of challenges to authoritarian regime; 2) as it happens everywhere with countries mired in domestic unrest and revolutions or civil wars, external forces can take geopolitical benefits from such conflicts either by supporting their proxies or even by directly meddling in the conflicts.

The ‘Kazakh winter’ didn’t prompt Central Asian countries to isolate themselves from Kazakhstan or from each other; on the contrary, they expressed moral and diplomatic support to Kazakhstan. However, the tokens of the second challenge – geopolitical – were observable in this case. The Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) forces were, for the first time, used in Kazakhstan, but not against an external aggressor but against internal rioters and protesters. Moreover, they were not operationalised for a dynamic military mission, but for the static tasks of guarding governmental buildings and the airport of Almaty. Activation of the sleeping military block coincided, accidentally or not, with exacerbation of tension between US/NATO and Russia and Moscow’s ultimatum delivered to the West on security guarantees. That ultimatum openly asserts that the former Soviet space belongs to the Russian sphere of influence and ignores the independence and sovereignty of Central Asian states.

In this geopolitical context, the main lesson of the hot days of the ‘Kazakh winter’ is that Central Asian countries must strengthen their regional unity and accelerate the integration process which would be the best response to the above-mentioned challenges: democratic reforms and the “test of unity”. Destructive geopolitics will undoubtedly undermine both democracy and integration in this region. Regional integration will be the best option to address these challenges. This scheme works as follows:

A) The recent past period of almost a decade of frozen regional integration, especially related to self-isolationism of Uzbekistan, demonstrated that it cannot but cause mutual mistrust and increase tension between and among the countries concerned. Such disunity can be capitalized by those geopolitical forces which pursue the “divide-and-rule” strategy and intend to impose upon the “conflicting” countries of the region its role of a mediator (CSTO’s January “mission” in Kazakhstan can be the hypothetical case or a prototype of such a scenario).

B) Authoritarian systems are by nature antagonists of integration. They can declare their co-operative stance and even support regional economic and trade cooperation, however, should some political disturbances occur in their country (like in Kazakhstan), they, in order to survive, appeal for help to an extra-regional allied great power, instead of democratically coping with such cases. Regional integration, in turn, can help create the common system of mutual assistance which will be free from geopolitical deviations.

In this regard, it should be mentioned that on 6th December 2021, the presidents of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan signed a Declaration of Alliance which was due to become a Treaty very soon. This document says, among other things, that their alliance is a key factor in strengthening peace, stability and security in Central Asia. The two sides expressed their determination to closely cooperate in the sphere of foreign policy and advance mutual interests and ideas of regional unification for the sake of securing pace and stability in Central Asia. They also stressed the importance of achieving mutually acceptable solutions of regional issues by Central Asian states themselves.

This Declaration was, in fact, an essential message to the region and to the world concerning the above ‘test of unity’. From this perspective, in particular, the creation of a regional system of mutual assistance and collective security would be of vital importance for addressing different intra-regional and extra-regional threats, including cases similar to the “Kazakh winter”.

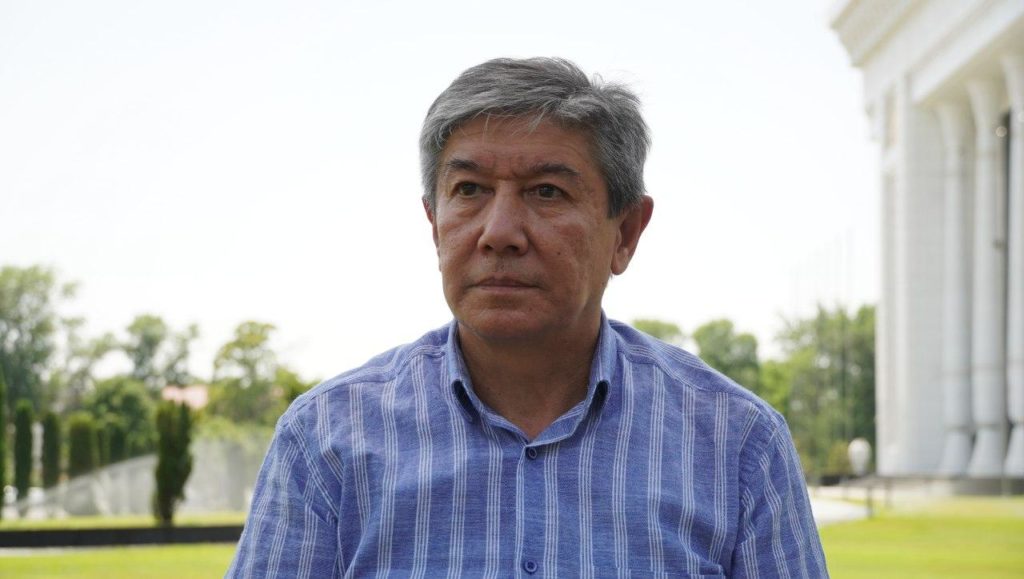

Dr. Farkhod Tolipov

Director of the Non-Governmental Research Institution “Knowledge Caravan”

Tashkent, Uzbekistan