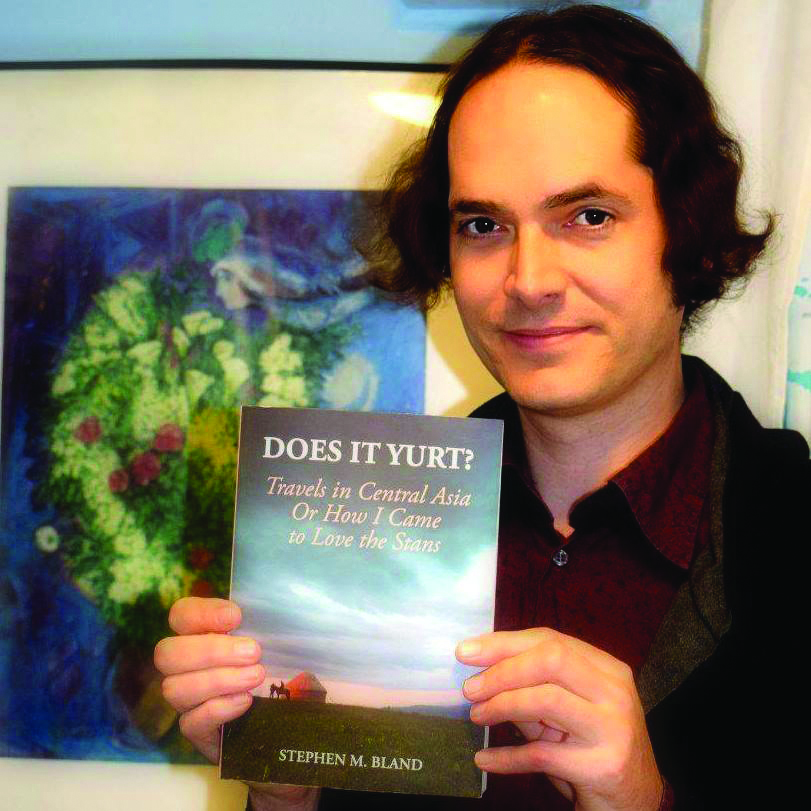

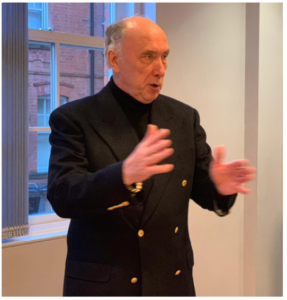

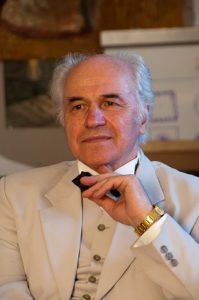

In Conversation: Shalva Natelashvili

Sixty-two year old Shalva Natelashvili is no ordinary Georgian politician. Born in the northern mountainous part of Georgia, he graduated from Tbilisi State University with a degree in Law before pursuing a post-graduate degree at the Diplomatic Academy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian federation. He began his career in the General Prosecutor’s Office of Georgia, later becoming head of the Department for International Relations. In 2004 he studied in the Leadership Programme of the US State Department earning an honorary position as envoy of the state of Louisiana. He is known to be a peace ambassador and founded the Georgian Labour Party in 1995 to help bring about change in his country after independence. OCA was fortunate enough to find a few spare minutes in his busy schedule to speak to him about his experiences and ambitions. We relay the conversation that Marat Akhmedjanov had recently with this man of change below.

OCA: You established the party in 1995?

SHN: Yes, I established party in 1995, but I have been in politics since 1992 – at that time I was the chairman of the legal committee of the Georgian parliament and the head of the editorial-constitutional commission in the country’s parliament.

OCA: You are not just staying in politics, but you are playing a very active role in politics. You participated in the presidential election, though your vote share percentage was reported to be low. Perhaps a disappointment?

SHN: Like in the Olympic Games, the important thing is to participate (he laughs). In 2002 we got 26% of the vote in the local elections. After that, in the parliamentary elections they have reported we achieved 12.5%, while in fact we understand we got 27%. And then, this damned revolution happened, and everything went backwards. In the first 2 years, there was a rise.

OCA: The leader of “Georgian Dream” party Bidzina Ivanishvili promised that they were going to reject the majority system and will move to a proportional election system, and they actually didn’t keep their promise. What do you think of this behaviour?

SHN: You know, in human history, that subject, the Russian billionaire, Gazprom shareholder, The Kremlin and Putin’s representative, will stay as a great “backstabber”.

I think you have heard the saying, I guess Churchill said: Politics is the ability to foretell what is going to happen tomorrow, next week, next month, and next year. And to have the ability afterwards to explain why it didn’t happen. But, what Ivanishvili promised to people was unprecedented. He promised invaluable money, promised zero bank percent, and now Georgia is in the first place for bank debts. He promised that there will be work for everybody; every village will have 5 million [dollars]; that all refugees and emigrants will be back home. But now he calls everybody to leave the country and find some job in Europe.

Of course, all this accumulated as a negative charge. And this charge accumulated and blew up on the night of the arrival of that poor deputy Gavrilov in Tbilisi, who was then the chairman of parliament. If this would have happened 5-6 years ago during the rating peak of Ivanishvili, then there would not have been such reaction. But, this time, people just blew up, obviously this was the reason.

At the same time, not a single statement was made by Georgia to the UN Security Council, because the government forbids it. And then all this blew up on the night of June 20, and the process of power change began together with the recognisable unrest. And this process was stopped only by a promise to hold proportional elections.

You see, in the world there are no precedents in a democratic system when deputies are elected from two different systems: proportional representation and majority vote. Furthermore both sit in the same house. Even in Russia, for this, there is an upper house, a federation council for majorities. We have it only in Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, i.e. when deputies elected by a mixed system are sitting in the same house.

My son was detained twice, he is the head of international relations of our party. The leader of our youth organization was detained, and other young people were detained, they all are held in prisons as political prisoners. Currently, the leaders of political parties have been arrested, they are in prison. Things got to the point where, for negotiations between the opposition and the government, international mediators were really needed, you know?!

There are only two countries in the world where the opposition and the authorities speak through international mediators – these are Syria and Georgia! It is a fact! That is why, you need to raise your voice.

OCA: On December 6, an opposition meeting was held in your office and a decision was made to hold protests throughout the country. And as you say your son was arrested. How long will these processes last, and what are you planning to join?

SHN: Opposition meetings are always held in our office. These protests will last until the departure of Ivanishvili and his group, and until the advent of a coalition government, a multi-party government, and the introduction of proper proportional elections. Georgia must get rid of this archaic voting system of majorities.

OCA: What is the role of your party in the opposition? Because, there are a lot of opposition parties now.

SHN: There are about 38 major opposition parties here. We have meetings here. We are happy that we were able to coordinate a very diverse Georgian political spectrum, that could not even sit together in one place for about 30 years. Because of this, sometimes we received coups, civil wars, serious conflicts and destruction. Thank God that the Georgian political mind has come to the point that for basic issues, you need to sit together at the same table.

OCA: It is a big deal that you were able to unite everyone in your office. But, it gives the impression that you are applying for a leadership role, or for some kind of intermediary role of parties.

SHN: No, no

OCA: What role do you see for your party then?

SHN: We are happy that we can unite all political forces to achieve one goal, and specifically to end oligarchic rule. As long as the oligarchs are in power, these pro-Russian – Gazprom, pro-monarchist or pro-feudal types, there will be no development in our country.

Now the situation is that the oligarch abolished the multiparty system. This refusal to accept proportional elections means: “You know, my dear parties, I do not need you, leave, I will look after everything myself. My henchmen lead their ministries, my appointees will talk in parliament about “great achievements” on your behalf,

OCA: Who is the main opposition? There are 38 parties, but which ones are the most significant and influential?

SHN: Almost all the main parties are here, and they are all equal at the same time. We simply have the function of coordinator-unifier in order to reach the final goal, getting rid of Ivanishvili. After this, there will be elections for which the parties will gain the majority, if they do not, then they will [have to] create something special just as in Germany where the most ancient enemies: Christian Democrats and Socialists united in one coalition government.

OCA: 38 parties sounds good. It speaks of pluralism of opinions in the country.But what are the main 5 parties?

SHN:It will be an unethical step from my side to name these parties now. Since this may cause some kind of conflict. I can’t do this at the moment. I can’t allocate any one of them. But, you can take a survey of the Republican Institute, where the main parties are listed there.

OCA: What are the main demands of the opposition except the departure of Ivanishvili?

SHN: After that, the parties will have a huge field for the implementation of their ideology. Of course, not a single ideology has been fully implemented in the history of mankind…

OCA: Speaking specifically about the Labour Party, what are your main objectives?

SHN: More specifically, it is de-oligarchization (from the word “oligarch”), an independent judiciary, real democracy, and not just in words, and social guarantees to people.

Now, unfortunately, in our country, a maximum of 15% -17% of the population use all the national wealth, and the rest live as secondary citizens. We want the country to create a middle layer that will control the politics, economy, legal system and future development of the country.

OCA: Regarding the Labour Party, what are your foreign policy aims?

SHN: By the name of our party it is clear that we are oriented towards Western values. In the 12th century, we already had signs of parliamentarianism, a special institution was created under Queen Tamar, in which laws were ratified. Similar principles created the famous parliament in Great Britain. And in the 17th and 21st years, when Georgia became independent, women in the UK did not have [fully equal] rights yet, but at that time we had not only female deputies, but also Muslim women (female deputies).

That is why, our historical values are Western values, but Asian values are not foreign to us, because Georgia was at the junction of Western and Eastern civilisation.

OCA: How do you see the organization of the country? Suppose you win the next election? And with which party is your party is ready to enter into an alliance with?

SHN-:We can enter into an alliance with all parties only if we lead the government. If this does not happen, then we will remain in constructive opposition, all the more we are used to this state, and we will control the actions of the authorities.

OCA: What is your attitude towards the Eurasian Economic Union?

SHN: I think that this is the worst model of the Soviet Union. You know why? During the Soviet Union, the center gave subsidies to the republics, that is, the republics lived and did nothing. They were just sent money from Moscow, and now we have to send money to Moscow.

OCA: What are your plans for integration with the European Union?

SHN: Our plans are very pleasant, we want to be members of the European Union, but unfortunately this is not quite achievable for us now, due to the geopolitical situation. Unfortunately, I want to repeat once again that France and Germany, while making decisions regarding Georgia, are following a very pro-Russian course. That is, they do not want to quarrel with Russia over Georgia.

Therefore, I am very worried that Britain is leaving the European Union. Leaving the European Union means inviting Putin as a host, because Putin has gas and energy for Europe in his hands. Energy decides a lot for the development of Europe and Asia. I respect the opinion of British voters who voted for Brexit, but that means they will give Europe to Putin.

OCA: In order for the opposition to win and be able to overthrow this regime, you need some kind of support in the regions. How strong is your party’s support in the regions? And in which particular regions do you feel support?

SHN: Our party has always had great support both in the regions and in the capital city. But, unfortunately, we were not able to establish real democracy, and at least count the votes correctly.

We have support in all regions, since the social situation in all regions is the same and they have the same interests. Despite the fact that Georgians are in the majority, an significant Armenian or Azerbaijani minority also live there. But unfortunately, in the regions, in which Azerbaijanis or Armenians live, there is also the factor of trade between the government of Georgia with Baku and Yerevan. That is, there is an agreement between the presidents, all these regions will vote for Saakashvili, for Shevardnadze, for Ivanishvili and all.

I am very worried because we have wonderful citizens of Georgia, Azerbaijanis and Armenians, some of the world’s famous figures who grew up here, who glorified Georgia and their historical peoples. And now they are deprived of the right to vote. Our main regions are Kartli, Kakheti, Imereti, Tbilisi, Rustavi. I repeat in all regions we have voters, and have always had them.

OCA: There is an opinion among experts that in reality the confrontation that is taking place in Georgia now is a battle of the oligarchic clans of Ivanishvili and Saakashvili. There is a struggle for power, for one it is revenge, in order to return. And Vashadze, it doesn’t matter, the first and second are his proteges.

SHN: Grigory Vashadze is the chairman of the national movement, he is a professional diplomat.

OCA: I don’t disagree but rather see a struggle between the two clans.

SHN: No, its Ivanishvili’s PR that, with the help of scarecrow Saakashvili, he can create personal immunity and eternity. There is a struggle of the people and the whole political spectrum against the oligarchic regime … By the way, the oligarchy is being destroyed from within, there are huge contradictions.

OCA: Ivanishvili, as you said, a Russian oligarch, a person who owned or owns businesses in Russia, and is affiliated with Putin. Is there any threat that Russia could take its side and in some circumstances occupy Georgia?

SHN: Russia has already occupied Georgia, 20% of the territory of Georgia is under the control of Russian troops. They are 300 metres from the main Eurasian highway, 300 metres, do you understand? So, if this continues, the political occupation is too obvious.

OCA: If you win and drive him out [Ivanashvili], will the Russian armoured personnel carriers come to his aid?

SHN: No, the matter will not come to this. Today the Kremlin is not satisfied, because it has not had its promises completely fulfilled. Shevardnadze played with both Moscow and Washington, then, both overthrew him, Bush and Putin. And Saakashvili had such a position, at first had excellent relations with Moscow, they agreed to create an anti-terrorism centre here, in Tbilisi. This is also a military base in Russia, and had excellent relations with Washington, and then took a pro-Western course and naturally this course continued. Putin was very dissatisfied, he considered that he had been “cut out” and burst here and there. Now the same situation is being established, everyone is tired of Ivanishvili. Everyone, this is a fact!

OCA: Now there are European MPs intermediaries whole have intervened, and they offered a mixed form, and it seems that the government is thinking about it…

SHN: Sorry, I do not trust these deputies. I still think that these diplomats are lobbying Ivanishvili.

OCA: You mean to say that these intermediaries protect Ivanishvili?

SHN: Not protect, but if there is an opportunity they will protect him and implement his interests.

These grievances are not directed to the whole of Europe, now I really appreciate that the deputies of the European Parliament arrived, that they recognised the existence of political prisoners, and told the truth. But there is a tendency, in the French-German bloc, which is always recognised by the Georgian government, and not by the people or the country, they are cooperating with the government, not with the opposition and all political representatives.

For us, Europe is like that. Due to the fact that we loved England/Europe, that is why we called ourselves Labourites, took the ideology of classical social democracy, the oldest one, thought that we would be partners, and embarked on the European path. They all failed and left us here alone against the oligarchs, Putin and against all this savagery.

OCA: It remains a fascinating and tense time. Thank you for taking the time to speak to us.